The Boston Biotech Watch Take on Google’s Healthcare Investing Approach Based on an Interview with Google Ventures’ Krishna Yeshwant

by Steve Dickman, CEO, CBT Advisors

Now that most private-company biotech CEOs have given up on “IPO window reopens” and “VC bidding war,” three of the most galvanizing words for someone raising money these days are “Google might invest.” Fund-raising for the CEO of a young biotech is always a war of attrition and corporate VC funds are the current weapons of choice.

It is one thing for cash-strapped management teams to want Google’s shiny new healthcare venture arm to invest. But should Google Ventures invest? Would it be the right thing for Google and the right thing for the sector if they came into more deals? We recently spoke to Google Ventures’ Cambridge-based healthcare representative Krishna Yeshwant, M.D., and we did some reading up on Google, including plowing through Ken Auletta’s widely reviewed (and bombastically titled) book Googled: The End of the World As We Know It “. Now here’s our take not just on what Google Ventures is doing in healthcare but also what we think they should be doing.

“. Now here’s our take not just on what Google Ventures is doing in healthcare but also what we think they should be doing.

(One caveat is that the bulk of investments that Google Ventures will do in the coming years will not be in the healthcare space. The fund ambitiously intends to invest $100M a year into startups and new ventures, and the vast majority of those dollars will flow into IT-related endeavors. Our focus is on the fund’s life sciences- and healthcare-related activities.)

Google Ventures would seem to fit right into the current dominance of corporate VCs within the universe of VC life sciences dealmaking. On the surface, it’s another cash-flush corporate fund wading into VC as part of a parent-company mandate to move up the food chain and generate insight as well as returns. (As if the “generate returns” part isn’t hard enough by itself!)

Google Ventures would seem to fit right into the current dominance of corporate VCs within the universe of VC life sciences dealmaking. On the surface, it’s another cash-flush corporate fund wading into VC as part of a parent-company mandate to move up the food chain and generate insight as well as returns. (As if the “generate returns” part isn’t hard enough by itself!)

We think Google Ventures (GV) actually does not fit the typical corporate VC mold at all and, based on its provenance, we think it has the potential to do amazing work. More about our views in a moment. First, we’ll look at how GV sees itself in the context of the deals they’ve already done. Then we will pull back and imagine what GV could do that might let it rise above and make a true mark on the healthcare investing and on healthcare itself.

Krishna Yeshwant, photos courtesy Google web site

Aside from cleantech, most deals lately in the life sciences and healthcare space are in therapeutics. By and large, GV does not do those. “We are probably not the investors to go after moving a molecule from Phase 2 to Phase 3,” GV’s Yeshwant said. “We are not ready to have a portfolio of molecules. [Furthermore,] it would be hard for us to invest in a single molecule.”

So what does GV do? So far, platforms, as embodied by GV’s first two healthcare deals: Adimab and iPierian. Although the former is on the East Coast and the latter on the West Coast, these companies have a few things in common. Both are funded by top-tier life science investors (Polaris, SV Life Sciences, Orbimed in Adimab; Highland Capital, Kleiner Perkins, MPM Capital in iPierian). Both are working on groundbreaking platforms and own enormous amounts of potentially valuable IP. Adimab works on antibody therapeutics; iPierian is a novel stem-cell-biology company with a big vision for overhauling the current clinical trials process by offering streamlined testing on ex vivo platforms derived from a patient’s own stem cells. There is more about Adimab’s and iPierian’s approaches in these linked news articles from Xconomy.

The companies differ in some key ways that give us some insight into GV’s parameters: Adimab is run by a charismatic and battle-tested CEO, Tillman Gerngross, who successfully sold his previous company GlycoFi to Merck in 2008 for $400M and thereby provided investors with a return of 9X or better. So in some sense, it’s a “bet on the jockey” play in the crowded space of antibody platforms. By contrast, iPierian is run by an experienced but not-quite-so-high-profile CEO, Michael Venuti, and in fact let go of its previous CEO, John Walker, the month before GV invested.

Tillman Gerngross, Dartmouth engineer extraordinaire

“We are clearly attracted to platforms,” said Yeshwant. “We can understand the science, we see the potential {for large exits} based on the early examples that a platform can produce. If there is room for the platform to go beyond what it is doing, we can REALLY get excited about it.”

Avoiding the corporate VC “bump”

In these cases, GV’s preference was not to invest in pure startups but to wait until some experienced investors took the early risk. In one or both of these cases, GV may have “paid up” in order to get into the syndicate. Lest that leave the wrong impression, Yeshwant hastens to explain: “Almost everyone at Google Ventures has started companies and looked at VCs from the other side of the table,” said Yeshwant. “I remember that: when a corporate VC comes in, you look at it as an opportunity to bump your share price. The way we are trying to place Google Ventures is really as an institutional investor. The track record we want to create here is not ‘here comes Google, let’s get a bump on our valuation.’ People LIKE to have us at the table. We are a VC firm that has [access to] a host of programmers and statisticians. We have former programmers on our team who can help our portfolio. Take our user interface experts, for example. This may not be relevant for therapeutics platforms but it might be very relevant for healthcare IT companies. That programmer’s role is to be dropped into some of those companies and create value.”

And yet neither diagnostics nor healthcare IT seem to be on GV’s radar screen yet. Yeshwant: “We are excited about the diagnostics field. We are watching it very closely. [But w]e have yet to find a great investment.” Most life science VCs who have looked at diagnostics would say the same thing – many more have looked than have actually done a deal.

When speaking of healthcare IT, Yeshwant reflects the melancholy wisdom of someone who knows the US healthcare system all too well. Yeshwant is in fact not only an experienced programmer and IT entrepreneur who has founded two companies that were sold to big IT players; he is also a current resident at Harvard Medical School working at Brigham & Women’s Hospital. “The healthcare market still does not really make sense [to us as venture investors]. Working in a hospital, we [as physicians] try our best to do what is right for the patient but the patient is only one of our customers. That distorts what [GV] as a service business [or investor in service businesses] can do. That setup does not let us get into this natural harmony of a company that can really serve the needs of the consumer and succeed because they did a good job by the consumer. As a medical doctor, I want to serve my patients, but it is very difficult to conceive of a great IT company [in this space]. There are so many needs IT can serve that would help patients. But what is the business model that does not involve so many confusing different stakeholders?”

Yeshwant has similar reservations about companies developing electronic medical records (EMRs) despite the inclusion of EMR subsidies in the stimulus and health care reform packages. “Despite a lot of money coming in from the government, it is not clear that the opportunity is really there yet,” he said. “Yes, that government money will drive M&A activity and there are ideas being thrown back and forth. We do not feel compelled yet by the companies we have seen.”

A common theme across all areas in which GV is considering is its very high bar for investing. Indeed, it has been nearly three months since our conversation with Yeshwant and GV has not announced a single new life sciences deal. Although it is inappropriate to draw conclusions from this absence of announcements (a flurry of new deals could be announced next week), the fund’s measured pace reflects the realities of being a VC in 2010 – when a lot fewer new-money deals are closing than in the years between, say, 2003 and 2007 – and the realities of being Google.

When we asked Yeshwant whether Google Ventures would prefer to start companies on its own rather than wait to be shown “doable deals” by the VCs in its network, Yeshwant cited the fund’s need to stay on the right side of its sole limited partner, Google itself: “Especially in healthcare, we are still looking for those [right] companies [for us]. We are looking for the entrepreneurs, the teams that will make those companies great. We are meeting a bunch of entrepreneurs and VC folks. If there is something we can put a good thesis around, then, yes we would be open to starting something, seeding a company and incubating it. We are still a bit early – we’d hate to hastily put something like that together and have it fall apart. That would sour Google proper. So for now we have to have a very high threshhold.”

Reluctance? What reluctance?

We think the threshhold does not have to be so high. This is where our recommendation comes in. From reading Ken Auletta’s book

We think the threshhold does not have to be so high. This is where our recommendation comes in. From reading Ken Auletta’s book

Googled: The End of the World As We Know It, we were reminded of Google’s roots and its winding path to $23 billion in 2009 revenues. The company is an advertising behemoth with now 99% of those revenues coming from ad sales. And the ethos underlying Google’s birth is still true for its many new ventures:

- We are engineers.

- We are scientists.

- We want to change the world.

Auletta’s book shows that Google is all about two mentalities: the engineer on one hand; the consumer-minded marketeer on the other. Sometimes – as when the founders built the first search engine – these are embodied in the same person. More often the roles are played by different people within the company’s leadership. The process works like this: the engineer comes up with an idea about what is technically doable and at the same time inherently elegant; the marketeer relentlessly orients it toward the “real user.” Born of a dynamic tension between these two forces, product after product has emerged from Google (think Google News, Google Earth, Gmail and Google Maps and) More recently, products and technologies have been acquired to take advantage of perceived opportunities (Android, YouTube).

Admittedly, it is hard to see how either mentality – better engineering, better consumer focus – will work in healthcare investing unless and until the healthcare system is reformed to be more responsive to incentives, more consumer-driven and especially more data-driven. The Google fund would seem to be able to apply its overwhelming leverage more efficiently in other fields – mobile computing, location-aware mobile apps, data storage and retrieval, even hardware – at least for now.

At the same time, the apparent hesitation by the GV team to do most healthcare deals and especially to start companies of its own – the “high bar” that Yeshwant was talking about in our interview – strikes us as inconsistent with the basic premise of the fund’s corporate parent. There seems to be a reluctance – if not an all-out refusal — to get too involved in truly risky deals that at the same time could be truly transformative. After all, in the letter that accompanied their 2004 IPO filing, the Google founders themselves wrote that they are looking to “make big investment bets” on technologies that have only a 10% chance of achieving a billion-dollar level of success. To paraphrase the loud, lascivious Sean Parker character in the hit movie “The Social Network,” “You guys think it’s all about making a million dollars?! It’s not. Think billion, baby!”

WWGD?

What we have heard from Yeshwant (echoed in this interview published by Wade Roush of Xconomy back in May, 2010) sounds not much different from what we hear from generic corporate VCs. What we’d love to see instead would look more like this:

- More attention from the top: You want to change the world, Sergey & Larry? Pay attention to healthcare.

- More experiments in combining bandwidth with healthcare. The Google project to “wire” a US city with ultrahighspeed broadband capability comes to mind. There have to be HC opportunities in that, perhaps in conjunction with an existing startup or a new one

- Pioneering programs outside the developed world that, for relatively low initial investments can improve upon technologies initially developed here and roll them out in developing-country markets. Then, when the “boomerang” comes back (see our earlier post on “boomerang” technologies), Google will be thinking ahead about how to make money on these technologies in the developed world.

- Start more companies! Forget the “high bar” and the “sour taste”. Instead, use your cachet and market power to start companies that might take a while to incubate but that can be truly transformative. This is already the approach of some top-tier US-based pharma company VC funds who have told us that they have grown impatient waiting for VC syndicates to form from the ever-shrinking pool of active VCs, so they’ve begun to dive in and fund the companies they want to see all by themselves.

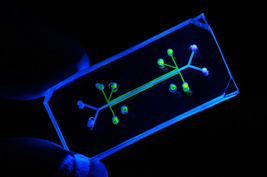

- Focus on diagnostics. Yes, Yeshwant said GV has not seen its favorite deal yet. But Yeshwant himself wrote an award-winning business plan for a company, Diagnostics for All, that could provide a valuable prototype. That company, which we highlighted in our blog post on “boomerang” technologies, is working on filter-paper-based diagnostic kits that can be manufactured for pennies. And Google founder Sergei Brin invested in personal genomics company 23andme.com, an investment now owned by Google itself.

- See our “shopping list” below for specific opportunities

We hope GV does all of these things. Because of its potentially long time horizon and its amazing market power in search and advertising, GV has a huge advantage over traditional VC funds. The exit from most of these businesses will be traditional ones – IPO or, more likely, trade sale – but another potential exit could be the creation of a new business unit for Google.

But not as many as there used to be

Right now, with the convergence of high-powered data collection through genomics and better sensors; better analysis of that data using high-powered computing; and a reorientation of the healthcare system toward prevention, there is no limit to what an active and visionary investor could achieve. To us, the potential for improving actual human health by taking advantage of available data is endless – and Google’s own track record in improving data access makes it an ideal player.

Therefore we’d encourage Google Ventures as follows:

- Think long-term, not near-term.

- Think big, not small.

- Focus more on strategic and societal benefit.

- Reach for the stars.

END

| TABLE 1: A HEALTHCARE SHOPPING LIST FOR GOOGLE VENTURES |

- Personalized medicine

- Computer-aided medical devices

- The “human-machine interface” in medical devices

- Electronic medical records

- Global health (investments in “boomerang” technologies would be perfect for GV – they will have the time & patience to wait for the boomerang to come back)

- Analysis of “Big Data” e.g. from patients or payers that could rationalize the US healthcare system or piggyback on the move toward comparative effectiveness

|