By Steve Dickman, CEO, CBT Advisors

December 10, 2012 (slightly shorter version originally published on TechnologyReview.com)

Quick biotech PR tip: When exiting stealth mode, heralding your company as the next Genentech is one way to get above the noise. That was the approach of Moderna Therapeutics, a Cambridge, MA-based startup that announced itself last Thursday, revealing that it had raised more than $40 million and attracted an all-star set of board members and scientific advisers.

Announcing that you just might be on the way to becoming Genentech II raises the bar a wee bit. And, at first blush, Moderna looks like it might even get over that very high bar.

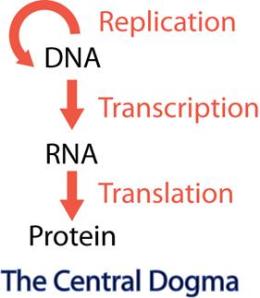

The concept is intriguing, to say the least. Biology’s central dogma is “DNA to RNA to protein.” Although Nobel Prizes have been won for discoveries that expand upon that central dogma (the discovery of reverse transcriptase, for example), the core approach underlies the first several generations of biotech products. Think EPO, Neupogen or the grandfather of them all, human insulin. You manipulate the DNA in the lab and then express the protein in the production facility. Then you put it in a vial and sell it to the patient, who gets an injection or an infusion. The main role for the dogma’s middleman, messenger RNA (mRNA), is a passive one: get transcribed from the DNA then, in turn, get translated into protein.

The concept is intriguing, to say the least. Biology’s central dogma is “DNA to RNA to protein.” Although Nobel Prizes have been won for discoveries that expand upon that central dogma (the discovery of reverse transcriptase, for example), the core approach underlies the first several generations of biotech products. Think EPO, Neupogen or the grandfather of them all, human insulin. You manipulate the DNA in the lab and then express the protein in the production facility. Then you put it in a vial and sell it to the patient, who gets an injection or an infusion. The main role for the dogma’s middleman, messenger RNA (mRNA), is a passive one: get transcribed from the DNA then, in turn, get translated into protein.

Moderna turns the dogma on its head: go straight to the RNA, do some fancy chemical tricks to it and deliver it directly into the body. This makes the patient herself into the production facility. All of us carry around cellular protein factories, known as ribosomes, and if properly activated, those can be harnessed (at a much lower cost) to produce proteins in which we have deficiencies.

One report on Moderna, published on Xconomy, quoted venture investor Noubar Afeyan of Flagship Ventures as saying that the company “builds on lots of things that have been tried before.” One of those things is gene therapy, providing genes (that is, DNA) via viruses or other delivery vehicles and trying to get cells to express those genes. Those approaches, too, tried to use the body as a manufacturing facility. Unfortunately, with some recent intriguing exceptions, most of them have failed.

Aside from this novelty, three things make Moderna so interesting:

Breadth of application

Since the mechanism is potentially so universal, proteins could be produced that address any number of diseases. The company said it will focus first on areas where protein therapeutics are already well-established: oncology supportive care, inherited genetic disorders, hemophilia and diabetes. But the company also claimed that it can also induce production of intracellular proteins that could never be given exogenously due to efficacy or immunogenicity concerns. Should this approach work, and it’s a bit of a long shot, it opens up new areas of application to the pharmaceutical industry.

Repeat dosing

Unlike many gene therapies, which could potentially be curative, in Moderna’s case the patient will need to be dosed with the mRNA over and over again. Think “recurring revenue stream.”

Intellectual property

When Genentech and Amgen were founded, neither one had a monopoly on the production of all human proteins in bacteria. When monoclonal antibodies were invented in Cesar Milstein’s laboratory in Cambridge, UK, Milstein was discouraged from patenting the concept. But in Moderna’s case, filing broad and deep intellectual property was the company’s central focus and a big reason why the company remained in stealth mode for the past two years. This means that even if other companies manage to enable the use of mRNA-based techniques in areas not yet explored by Moderna, the company could still demand royalties.

Yet another reason to pay attention to Moderna: unlike many other biotech companies, Moderna was not based on work published soon after its founding. The original publication that drew interest from Afeyan didn’t involve using patients as protein factories at all. The paper, published by company founder Derrick Rossi in 2010, involved using injected mRNA to produce cells that resemble embryonic stem cells. According to the Xconomy article, Afeyan did not want to invest in a stem cell company, which he perceived as too risky. Instead, he suggested that Rossi use the mRNA as a way to induce protein production in patients. That led to the key experiments, as yet unpublished, that were the basis of the company’s intellectual property and its initial financing. According to Moderna’s triumphant press release, the publications are supposed to come in 2013.

At the same time, there are three big questions:

Delivery

Isn’t Moderna facing a double hurdle, first in selectively getting into the right kind of cell and then in achieving the right therapeutic dose level? The first of these hurdles represents the same kind of delivery problem that has presented such an enormous challenge to RNA interference (RNAi) companies like Alnylam. For all its promise, RNAi was born amid a hail of questions expressing doubt about delivery. How to use systemic delivery to propel nucleic acid molecules with strong negative charges and potentially vulnerable to ribonucleases into the right cell types in the right organs at high enough concentrations to have a biological effect? That was the question. (The early results, as I viewed them in a cramped biochemical laboratory in Kulmbach, Germany, in 2002, looked blotchy at best.) More than ten long years later, despite some powerful efforts that cleverly take advantage of biological reality, for example, the “leakiness” of tumors, those questions have still not been completely laid to rest.

The other part of the delivery challenge has to do with what happens to the mRNA once it is inside the right kind of cells. How many cells exactly has it penetrated? What are the expression levels over time of the desired proteins on a per-cell or per-tissue basis? Will the levels in one patient be the same as in the next one? Achieving appropriate dosing without setting off alarm bells at the Food and Drug Administration will be tough.

Where are the other investors?

The only institutional investor named in the press release was Flagship Ventures. If other VC firms were involved, one would expect to find them sharing the limelight. So either Flagship decided that what it had in Moderna was so good, it did not want or need to share or other VC funds were approached and said no. It will be interesting to learn over the coming weeks which of these explanations, or which combination of them, pertains.

What’s the value in its first applications?

Let’s assume that the Moderna approach works. Suddenly EPO, Factor VIII and beta-globin can all be produced in patients deficient in these proteins simply by dosing them regularly with mRNA. But so what? There are already therapies on the market that will be doing this. In fact, some of those will be going generic and will be joined on the market by “biosimilars” that will presumably cost less than the existing (expensive) drugs. Furthermore, many of today’s most successful protein therapeutics have been modified (e.g. pegylated) to improve their half-lives. Where would be the advantage of an injection of mRNA over one of protein, especially a second-generation, long-acting protein such as Amgen’s Neulasta®?

Perhaps the advantage would come in proteins that cannot be injected as such because they elicit unwanted immune reactions from patients. But there are not too many examples that come to mind (thrombopoietin is one). That might be one reason why Moderna CEO Stéphane Bancel said that the company would be partnering the largest-market indication areas, like cancer, while retaining only rare diseases (in which intracellular protein production might make sense) for itself.

In summary, Moderna reflects a novel approach. For that, its founders and visionary investors deserve their well-earned day in the spotlight. It is especially commendable that a venture investor in the current no-whip, Splenda-only funding environment would create a good old-fashioned full-fat latte of a biotech company. Funding it exuberantly, vigorously protecting the IP and keeping the shares to yourself are all probably wise moves. But for the rest of us to see Moderna as a new Genentech, Moderna will have to publish in a peer-reviewed journal, partner with a pharmaceutical company or at least explain how it addresses basic questions like delivery and consistent dosing across tissues and patients.

# # #