By Steve Dickman, CEO, CBT Advisors

What’s the next key population for personalized medicine? We’ve got it: not those with hereditary disease nor those with chronic conditions. Not even anyone who is sick, well, young or old. It’s the not-yet-conceived.

As the New York Times reported on the front page in January, the Redwood City, California-based company Counsyl is offering to prospective parents a unique, one-price panel of SNP-based tests for over one hundred genetic diseases, including cystic fibrosis, Tay-Sachs, spinal muscular atrophy(SMA), sickle cell disease, and Pompe disease. Pay $349 a parent and you too can learn whether your offspring will be at risk for these diseases and a host of other single gene disorders.

Based on our understanding of the genetic testing space and on the information available about this company, it seems like Counsyl’s test, on the market for several months, is in a position to do very well. After all, assuming the testing is done accurately and discreetly, what parent would not like to put his or her mind at ease by quantifying this risk?

But the very ease-of-use and consumer friendliness that make the test appealing as a commercial proposition raise intriguing questions about the ethical and societal implications of such screening tests as their availability and scope grow.

This post comes in three sections: we will first describe what Counsyl does, how it differs from existing genetic testing services and what its business advantages and challenges might be. Then we will consider some of the societal and practical concerns raised by experts in medical genetics and bioethics whom we have interviewed on this topic. Finally, we will look to the future of pre-conception screening to consider the implications if techniques providing higher information content – especially full sequencing – are brought to bear on the specific market segment of would-be parents.

As our readers know, we are most eager to shine our light on a personalized medicine company if it is viable as a venture investment. Counsyl has not raised VC money and may never need to do so, but after the usual important caveats (e.g. about cost of sales, gross margin etc.) it sure looks like a “doable deal” to us. In two angel rounds reported on the SEC Web site, Counsyl has raised a total of $4.9 million in angel investment. The company declined to be interviewed for this post.

What makes Counsyl look like a good deal? We continue to believe strongly in the criteria we laid out, courtesy of Dion Madsen, GP at Physic Ventures in San Francisco, in our mid-December, 2009, post entitled “Medicine Gets Personal – But How Do VCs Make Money?” These require that a potential investment be

1. Actionable – it informs a decision around treatment, preventive action or behavior

2. Cost-effective

3. Based on validated science; and

4. Clinically meaningful.

Based on these criteria, Counsyl’s test passes with only a few small hesitations.

Actionable

Once handed the results, potential parents – married couples, unmarried people considering having a child together or even customers at sperm banks – could choose not to conceive (e.g. to adopt instead) or to go through in vitro fertilization (IVF) followed by preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD). Counsyl’s customers could in principle even select a mate based on whether the person carries risks for the hundred or so genetic diseases in Counsyl’s panel. Other actions are possible and will be addressed below.

Counsyl claims its test will save thousands and be reimbursed by insurers

Cost-effective

The company’s price point of $698 per couple is low given the many tests it offers. Tests for some of the most common diseases on the list, such as Tay-Sachs disease, can cost $100 or more when tested for alone or in combination with a small number of other diseases. At just $349 a person for Tay-Sachs and a hundred other diseases, Counsyl’s test would seem to be a bargain.

Based on validated science

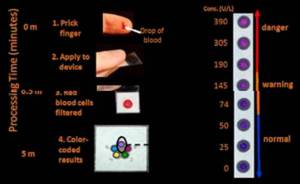

This one is harder for us to judge. But all of the diseases listed on the company’s web site can be tested for with a simple (in the jargon of genetic testing, a ”SNP-based”), rather than a complex (“sequencing-based”), test. In many cases, such as sickle cell disease, a large majority of carriers have just a one-base-pair mutation in their genetic code. A blood test or, in this case, a saliva test ought to be highly effective at identifying carriers with a high degree of confidence and without a large number of false positives. (The web site claims greater than 99.9% sensitivity and specificity i.e. virtually no false positives or false negatives). And of course, in every case where there is an initial positive result, a confirmatory test can and should be performed.

Clinically meaningful

This is the toughest one of all. We have to consider at least two scenarios: How meaningful is it to know in advance that one’s child would have a 25% or greater chance* (See Footnote) of being afflicted with a genetic disease? And how meaningful is it to know if the child has a chance to wind up a carrier?

PGD for all – except Ethan Hawke

The first scenario is more important – it represents the raison d’être for the test. We’ll look at both below.

Business challenge: barriers to entry

But before that, let’s consider a business challenge: competition. There do not appear to be too many barriers to entry in this area of genetic testing. Counsyl probably does not even own the rights to the DNA underlying most of the tests included in its panel. Even if Counsyl strikes deals with patent-holders on single-gene diseases, DNA “ownership” is under siege. Indeed, in a controversial court ruling on March 29, 2010, a U.S. district court judge struck down the patent protection of Myriad Genetics on the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility genes BRCA1 and BRCA2. This ruling, which will undoubtedly be appealed, opened the door to even wider competition on diagnostic tests than before. Large-scale reimbursement will provide a more meaningful barrier than any other; it is still too early to tell how widely the Counsyl test will be reimbursed by insurers.

Now back to the question of whether the Counsyl test is “clinically meaningful.” First, consider the case where both prospective parents turn out to be carriers of a (recessive) gene for a devastating and untreatable disease like spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a motor neuron disease related to ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease) that is often fatal in early childhood. The parents’ carrier status puts their offspring at 25% risk for inheriting the disease. Parents who know that might choose to undergo IVF and PGD or to adopt instead of having biological children.

Indeed, carrier screening for specific diseases in specific populations has been widely adopted even when it is more expensive and less revealing than what Counsyl is offering.

Take cystic fibrosis (CF), for example. This genetic disease causes the accumulation of sticky mucus in the lungs as well as digestive problems. Life expectancies have increased from the teens and twenties all the way up to thirty-seven but given the option, many parents have avoided bringing children into the world who have a high chance of having CF. Kaiser Permanente recently was reported by USA Today to have identified 87 couples who were among the 10 million CF carriers in the United States, and when their fetuses were tested, twenty-three were found to have the disease. Seventeen of these were shown to have the more severe form of the disease and parents chose to terminate sixteen of those pregnancies. Four of six pregnancies were terminated in cases where the fetuses were shown to have a less severe form. More broadly, USA Today also reported that couples who were informed after prenatal screening of genetic disease present in their offspring-to-be chose to terminate pregnancies about fifty per cent of the time.

For many parents, the pre-conception decision to adopt or to undergo the rigors and expense of PGD is much less problematic – and perhaps more consistent with their religious or ethical beliefs – than the decision to terminate a pregnancy. Indeed, both advocates and opponents of prenatal screening might be able to agree that there are advantages that this type of pre-conception screening provides.

For a case in point, think about the Ashkenazi Jewish population which is prone to severe genetic diseases including Tay-Sachs because of founder mutations in the early (small) Eastern European population combined with the tendency especially of orthodox Jews to marry within their group.

The scourge of Tay-Sachs disease, which is typically fatal in early childhood, is what prompted Rabbi Josef Eckstein to found Dor Yeshorim, a Brooklyn-based group that offers free blood tests to Jews. Before he started Dor Yeshorim, Rabbi Ekstein lost four children to Tay-Sachs. He told USA Today “I am a Holocaust survivor. I was born in the middle of the Second World War. I hope that I am not a suspect for practicing eugenics. We are just trying to have healthy children.”

Eugenics in a new light?

Dor Yeshorim said it has 300,000 members and has branched out to test for not only Tay-Sachs but eight other genetic diseases including CF. Tay-Sachs births are down to about a dozen a year in the United States. “In the Orthodox Ashkenazi community around the world, we have virtually wiped out the diseases we screen for,” the group’s development director Allan Binder told USA Today.

Downstream consequences

But what Counsyl is selling is the opposite of targeted. It calls its product the “Universal Genetic Test,” which is a bit of a misnomer given how many genetic diseases (thousands) are NOT included in the current panel. The idea is that the test be offered as broadly as possible. Over a hundred U.S. clinics are providing the test and Counsyl claims that it is already being reimbursed by insurers. Customers can even mail in saliva samples and receive their results directly.

In interviews with Boston Biotech Watch, medical geneticists and ethicists raised concerns about Counsyl’s test based in part on this accessibility and ease-of-use. Whereas the test itself is “actionable” since it can lead to a decision to pursue adoption or PGD, the PGD route is “extremely expensive, burdensome and risky” said Gail Geller of Johns Hopkins University’s Berman Institute of Bioethics . IVF cycles cost $10,000 each and PGD thousands more (e.g. reported at $5,800 on the web site of an IVF clinic in California. IVF is covered in some states (e.g. Massachusetts and New Jersey) but in most U.S. states and most other countries, it is paid out of pocket.

This leads to another objection from Geller: that the downstream consequences of screening, including IVF and PGD procedures, raise not only cost issues but also “other weighty issues such as … access … [and] deleterious effects on people who undergo it. We don’t even know the long-term effects of [the ovarian] hyperstimulation” required for IVF.

Of course, adoption and PGD are not the only potential actions that can be taken following a positive signal on the Counsyl test. Another likely – if controversial – action for some couples will be to test the fetus early in pregnancy (for example with chorionic villus sampling – CVS – which is already indicated for women with high-risk pregnancies) and terminate in the event of a positive test. Some would argue that this route preserves the fifty to seventy-five per cent of offspring who would not have been born with the disease in question. But that decision comes with a price, terminating a pregnancy, likely to be too high for some.

Michael F. Murray: A Screen Too Far? Photo courtesy Partners Healthcare Center for Genetic and Genomic Medicine

The actionability of Counsyl’s test was also questioned by Michael F. Murray, a medical geneticist at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and a faculty member at Harvard Medical School in Boston. Murray says that the all-comers access to Counsyl’s test means that “they are doing genetic screening for people who have no reason to be screened.” This can lead to issues with the outcomes of the tests. “Doing a cystic fibrosis test in an African-American or a sickle cell test in a Caucasian-American, you will get a very low yield from those tests. When you come up with a positive in those settings, it will be hard to interpret it.”

Both of these sets of objections are reminiscent of some criticisms of 23andme.com, Navigenics and other “consumer genomics” companies. Those companies offer similar DNA-based tests for adults and then reveal genetic predispositions for everything from diabetes to ear wax type. Lately, the popularity of 23andme and its peers has seemed to stall, according to the New York Times. Actionability is a big reason. After the novelty of knowing one’s predispositions has worn off, is life really all that different?

In that regard, the Counsyl test is “more actionable than all the other genetic platforms like 23andme” said Santiago Munné, Director of PGD at The Institute for Reproductive Medicine and Science at Saint Barnabas in Livingston, NJ. After all, what could be a more decisive action than choosing not to have a child at all?

Munné, who agreed that his practice stands to benefit if the Counsyl test is widely adopted (“for my business, this is great,” he said), was also not concerned about the potential for false positives and other inaccuracies in the Counsyl SNP-based test. “For at least 90% of what we test for, the SNPs are the real mutation.” Furthermore, “they can always do a more rigorous test like PCR” if a SNP-based test comes up positive.

Too much information?

Perhaps the largest question raised by the experts about more extensive pre-conception testing concerns anxiety. When a couple are told, for example, that their child will not inherit a genetic disease because both partners are not carriers but that there is a likelihood that the child will him- or herself be a carrier, what does that mean? Most couples would likely go ahead with a pregnancy upon being informed of carrier status. After all, every one of us is a carrier for something. But the same way that learning one’s own genetic predispositions via a 23andme.com or Navigenics or Decode Genetics test may provide “too much information” and not enough meaning behind it, learning that about one’s potential offspring might be even harsher.

Geller, Murray and others expressed even deeper reservations about the likely next stage for pre-conception genetic testing: full sequencing of both prospective parents. Counsyl does not offer sequencing-based tests but other seed-stage companies have come to our attention that are considering doing so. None of these companies has emerged from stealth mode, so the comments here about sequencing-based tests can be considered speculation. On the other hand, the cost of sequencing is dropping rapidly. The $1,000 genome seems just months away. And has there ever been a medically relevant technology that was developed but not used?

The pre-conceived genome

Concerns about sequencing in the pre-conception setting run parallel with concerns about whole-genome sequencing in general. There is a “triple whammy” with sequencing in this setting which makes the observers’ concerns even graver: that sequencing provides much information that is NOT actionable; that therefore, the more data there is, the more anxiety it will create; and that THIS patient population above all others is prone to irrational decision-making and costly second-guessing none of which can really provide the answers the couples are seeking.

“Going to full sequencing would represent a disproportional increase in data and a decrease in the understanding of that data,” said Murray. At least the SNP-based data in Counsyl’s test will be more focused than that. “SNP data will tell you “yes or no” at 500,000 points or whatever it is,” Murray said. “Sequence data will come up with all kinds of variation. We will know even less about how to interpret a lot of that. In fact, people are starting to talk about the $1,000 sequence followed by the million dollar workup.”

Other medical geneticists concurred because of the nature of the customer population. Murray said, “Those couples tested are going to be frantic with whatever the data is. They will be seeing ten specialists to talk about ten diseases that they never heard of before and it will be an unclear risk to begin with. So I think that that model [of pre-conception sequencing] will generate tons of downstream costs with uncertain benefit.”

This concern dovetails with the one we alluded to earlier: what does a couple do with the knowledge that their child will likely be a carrier of some severe disease? Isn’t that the kind of knowledge that couples might rather not have? Will Counsyl have to begin to offer more limited test results telling parents only when their offspring have the potential to have these diseases rather than just carry a gene for them?

Prof. George Church, sequencing proponent

We contacted George Church, a Harvard professor and sequencing technology innovator, one of the first people to have his genome sequenced and the results published as part of the Personal Genome Project. Church is professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School and also heads the Lipper Center for Computational Genetics there. To Church, the dichotomy between SNP-based tests and sequencing-based tests is not going to be around for long. “Many medical genetic traits have a large enough number of genes and alleles that are highly predictive and actionable,” Church wrote in an email message. “It is more than fit onto a simple chip, and the list grows at a rate that is hard to update with chips but easy to update with sequencing software.” Examples he cited include the hereditary eye disease retinitis pigmentosa, which can cause blindness, and BRCA1 and BRCA2, which are linked to risk for breast cancer.

Furthermore, Church said, “sequencing is routinely used for many/most clinical genetics right now (e.g. Myriad Genetics [and its BRCA1/BRCA2 test]).”

Church also rejects the concern about causing anxiety to prospective parents. “This sounds paternalistic,” he wrote. It is “as if patients and doctors aren’t able (with appropriate fact sheets or software) to combine diverse data to get better predictions — and for many variants wait for new research or new symptoms. Perhaps we should start implementing safeguards against economically incentivized overinterpretation rather than against low cost multiple tests.”

Church’s argument echoes one heard widely by advocates of personalized medicine on the merits of decentralization. By putting the data, however ambiguous and anxiety-provoking it is, into the hands of the customers themselves, Counsyl allows each person to choose exactly how to respond, if at all.

A business or a public health measure?

The next objection puts the Counsyl offering into perspective. When asked whether the Counsyl test – cheaper, more comprehensive and available even to people who live far away from the nearest diagnostics lab – was actually a net benefit for society, Murray said, “It’s true that if you screen everyone in the world, you will help some people who might otherwise not have been helped. But,” he continued, “it is a business plan and NOT a carefully considered screening plan.” From a public health point of view, pre-conception screening might be done very differently.

Ramji Srinivasan, 28, Counsyl’s founder-CEO

We agree with that. Counsyl is a business. It has been set up to provide a return for its investors. And like so many other experiments to come in the world of personalized medicine, Counsyl has isolated just one market within many and resolved to address it very thoroughly. Counsyl’s business plan seems to follow “Entrepreneurship Rule 101” very well: focus, focus and focus some more.

We also have to remember that the Counsyl test is a “1.0” version, with all the potential for bugs and subsequent improvement. The next generation of Counsyl’s offering might be much more sophisticated, offering more nuanced results for specific customer subgroups both inside and, eventually, outside the United States. (Newsweek reported in December, 2009, that the government of Taiwan is considering offering reimbursed access to the Counsyl test to its entire population.) The “2.0” version may well contain even more tests since, as Murray put it, “there is a tidal wave of these tests coming.”

A final ethical issue we see even thought our sources did not emphasize it is the “designer babies” question: the Counsyl test, especially as later versions of it incorporate more and more disease-causing genes, strongly supports a world-view that says human beings can control their destiny by controlling the gene pool. The free market in genetic data exploited by Counsyl accelerates humanity on a path down the slippery slope toward attempts to control IQ, weight, height and other factors, much the same way that in some cultures, the most sought-after piece of genetic data about a future offspring is whether there is a Y chromosome present i.e. whether a baby will be a boy.

They’re my genes, and I want to know what they are

Counsyl seems to have made a strong start, giving it a “first-mover advantage” toward grabbing a big share of a new and growing market. Personal genomics companies like 23andme and Navigenics – whose DNA tests are after all based on the same technology and priced in the same range of a few hundred dollars – might well be kicking themselves for not getting to these customers first. It may be that the customers who are most anxious about the results of a test like this are also those most eager to pay the fee, get the data and then decide what to do with it.

# # #

*According to the rules of Mendelian inheritance, so-called “recessive genes” (more precisely “recessive autosomal variants”) that also breed true (i.e. that have “high Mendelian penetrance”) lead to a 25% chance that an offspring will have two copies of the disease gene and thus have the disease. If the disease gene happens to fall on the X chromosome, the likelihood is 50%. In cases where the disease emerges haphazardly rather than predictably (i.e. of “incomplete penetrance”) and of multi-gene traits (QTLs or “quantitative trait loci”), the likelihood of disease would be lower and would vary widely.