By Malorye Allison* and Steve Dickman, CEO, CBT Advisors

We always thought that innovation in biomedical science started in western countries and pretty much stayed there, where the money is. The role for developing countries, if they ever got their hands on new biomedical technologies at all, was as consumers, not innovators, and not exactly desirable consumers at that.

But lately we have noticed a countervailing trend. We call it “the boomerang”: technologies invented in the developed world that are designed (or re-designed) to work better, cheaper and more efficiently in developing countries. Once every extra penny has been shaved off the cost of goods; once the moving parts have been reduced to the bare minimum to stand up to harsh conditions or other demands; and once the innovations have been adopted by thousands if not millions of consumers, then, their owners figure out how to reintroduce them to the countries whence they originally came.

We are far from the first to observe that the United States is burdened with excess regulation, perverse incentives and entrenched interests barely affected by the recent insurance reform, which was mislabeled “health care reform” (HCR). At the same time, we observe burgeoning opportunity and a willingness on the part of both U.S.-based and developing-world inventors to focus on the less affluent but larger markets outside the United States and Europe. This is turning the markets of the developing world into hotbeds of innovation.

The limitations on implementing new healthcare technologies and delivery approaches in the United States are well known. We will give a couple of examples later on of how new technologies outside the boundaries of reimbursed care (think iPhone apps and Facebook) are leapfrogging the current U.S. healthcare system. But first we will look at some new technological and business innovations in healthcare that are getting their start or at least a big boost elsewhere.

Our thinking about this topic began with a visit to the recent World Health Care Congress (WHCC). This, backed up by an Economist article, convinced us that we are onto something. Some of the next radical or gentle upheavals in surgical techniques, medical devices and healthcare delivery may start in the labs of Minneapolis and Mountain View but then they will be tested and optimized in India, Mexico, Bangladesh and Africa. Eventually, if we are lucky, some of them will return.

At the World Health Care Congress in Washington in early April, we heard Harvard Business School professor and author Clayton Christensen give a fabulous set of talks. Christensen, whose 2009 manifesto The Innovator’s Prescription: A Disruptive Solution for Health Care , coauthored with Jerome Grossman, M.D. and Jason Hwang, M.D., was a sensation in healthcare circles, said that US health care “reform” legislation did nothing except to “cement the current unsustainable model.” He said that nothing innovative can really happen in the United States for another ten to twenty years (!). But what’s happening in India and Africa is stunning, he said. “When you have no other options, that’s the perfect model for innovation.”

, coauthored with Jerome Grossman, M.D. and Jason Hwang, M.D., was a sensation in healthcare circles, said that US health care “reform” legislation did nothing except to “cement the current unsustainable model.” He said that nothing innovative can really happen in the United States for another ten to twenty years (!). But what’s happening in India and Africa is stunning, he said. “When you have no other options, that’s the perfect model for innovation.”

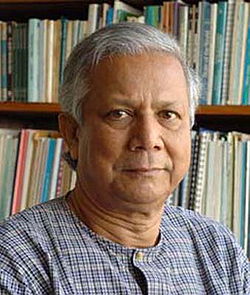

In another WHCC talk, Grameen Bank founder and Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus pointed to a similar phenomenon. The new paradigm he cited: Build cheap practical versions of high tech tools and clinics that focus on a narrow range of badly needed treatments: think “surgery factories.” Here, the innovation focuses as much on the process of care delivery as it does on the care itself, reminiscent of the “business model innovation” cited by Christensen in The Innovator’s Prescription as one of the key needs of the U.S. healthcare system.

Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, founder of Grameen Bank

Consider eye surgery, ironically one of the profit centers for physicians even in countries like Canada which have “socialized medicine.” In India, for example, Aravind Eye Hospitals can offer $25 cataract surgery. Each doctor at Aravind does about 2000 surgeries a year. As The Economist put it in its startling April 15 survey of developing-world innovation “The World Turned Upside Down”, “Aravind [is] the world’s biggest eye-hospital chain [and] performs some 200,000 eye operations a year. It takes the assembly-line principle literally: four operating tables are laid side by side and two doctors operate on adjacent tables. When the first operation is done, the second patient is already in place.” The price is lower, but the process is still profitable. What a refreshing thought for those of us in countries like the United States, where each incremental innovation feels exponentially more expensive!

Then consider the upstream impact of such massive scale: costs must be lower, so technology must adapt. Krishna Reddy of Care Hospitals said at WHCC that his organization looks at every opportunity to lower costs. When designing a device for heart surgery, for example, they try to make only the part that will touch the heart disposable. In many cases, Aravind and Care have found ways to manufacture their own devices more cheaply than their first-world cousins.

LifeSpring Hospital in India

Then look at childbirth. Elsewhere at WHCC, we heard about birthing centers created by LifeSpring in India that, according to The Economist, have reduced the cost of giving birth in a private hospital to $40 by looking after many more mothers. They charge $1.60 for a consultation with a physician and about $38 for an average delivery. They are teaching the people WHY there is value in paying for a delivery (versus mother and child possibly dying on a dirt floor out in the middle of nowhere). They market to husbands and mothers-in-law, and they paint the places cheery colors and make them comfortable and appealing. They are profitable and expanding, and the patients demand quality care for the price, which is of course well below the Western market price. Of course, we surmise that care is available so cheaply only via “paraskilling” e.g. deliveries by midwives or nurses, with physicians in the background if needed, which is not (yet) allowed to such a great extent in the developed world.

How about the business of healthcare? Take electronic medical records, for example, which received a chunk of government support in the US HCR package. India is rolling out a smartcard that can be printed up in any village and contains biometric information along with the patient’s health record. Standards are imposed from above: Local governments have to make sure these cards can be read anywhere if they want to get their share of government funding for the program. About fourteen million cards have been created already and the goal is to get one for each of the 300 million Indians who qualify for this plan, specifically – and only – those poor workers who tend to move a lot. Interestingly, Anil Swarup, Director General in the Indian Ministry of Labour & Employment, said in his talk at WHCC that it is important to charge something, not nothing, otherwise patients don’t think the service has any value and won’t use it. Furthermore, charging something, even very little, shows respect for the patients’ dignity. Swarup claimed that a large part of the project’s success was due to his complete naivete regarding health insurance. Certainly, no one anticipating the usual landmines would have attempted something as simple and yet far-reaching as he appears to be well on his way to achieving.

As more users are brought into the healthcare system, this drives up demand for “low-tech” services such as cheap, practical, point-of-care diagnostics. That theme came up again in a recent lecture by biotech financier and big-picture thinker Stephen Burrill held at MIT on April 14. “China passed its own health care reform in April, 2009,” Burrill said. “They want to provide healthcare for all 1.2 billion of their people.” Just think of the economies of scale! Innovation in low-tech areas such as healthcare delivery will be massively rewarded.

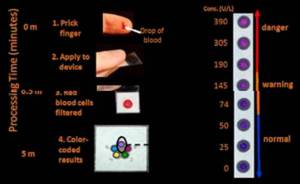

Consider three low-cost healthcare innovations from the developed world described at the World Health Care Congress:

- Mobisante’s smartphone/ultrasound device: Mobisante has developed a smartphone that can serve as an ultrasound scanner. It stores information, sends images to hospitals for diagnosis, and employs a touch-screen interface

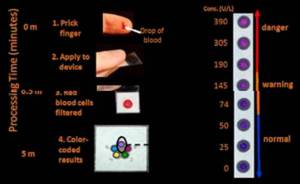

- Diagnostics for All’s postage-stamp sized, paper-based “laboratory.” (This device won the top award at the event.)

- Voxiva’s mobile phone platform for transmitting key messages among healthcare providers, for example to allow care providers in Rwanda to keep their clinics stocked with vital HIV/AIDS drugs, medicines that would routinely run out in the pre-cellphone era. This company was the subject of yet another Economist article

We’ll look at each of these one at a time along with a look at how two boomerangs have already begun to return.

Mobisante: the smartphone-based ultrasound

Mobisante is based in Redmond, WA, and run by Sailesh Chutani, a former Microsoft executive. It has developed a smartphone that can serve as an ultrasound scanner. It stores information, sends images to hospitals for diagnosis, and employs a touch-screen interface. The first market for the device is the developing world, where its makers say seventy per cent of people cannot get access to ultrasound services. The device will cost approximately $5,000, which may still seem steep by developing nation standards, but will be attractive to public health departments and NGOs, since having access to ultrasound is to vital to many medical diagnoses. Chutani predicts the device will allow ultrasounds that cost less than $1 a patient.

Boomerang: In his talk at WHCC, Chutani said that their next market will be primary care physicians in the developed world. While the device doesn’t replace high-end ultrasound equipment found in most U.S. hospital radiology departments, it is perfectly suitable for taking “a quick look” for example to confirm a pregnancy or determine that a baby is in the breech position. Such devices could thus expand the range of services that primary care doctors do, taking business away from specialists. This could be especially important for the twenty million (!) patients in America treated in community health centers. The needs of this community have traditionally not been the main focus, to say the least, of big-company health care technology developers but that seems to be changing as we shall see below when we come to General Electric.

Mobisante’s ultrasound smartphone

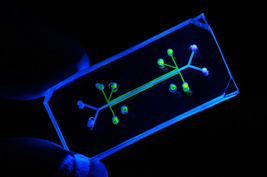

Diagnostics For All’s paper diagnostics laboratory

For a former venture capitalist who used to attend an annual “lab-on-a-chip” conference that was all about silicon, glass and plastic, the appearance of a lab made of paper from Diagnostics For All (DFA) comes as a bit of a shock. It apparently impressed the jury of the WHCC poster competition, which awarded DFA the conference’s top prize. But there it is: a network of channels on a single tiny device routing blood, urine or other bodily fluids to tiny assay spots that give easy-to-detect color readouts. The product is based on the elegant microfluidics and materials science work of the serial biotech entrepreneur George Whitesides of Harvard University and the company’s board is studded with some of Boston’s biotech elite, e.g. former Vertex CEO Josh Boger. According to the non-profit’s web site, the nearly-all-paper chips are “designed for resource-poor settings”, are “less expensive to manufacture and deploy than alternatives” and are intended for populations that would otherwise have no access to the high-tech wonders of the modern diagnostics lab.

The DFA lab-on-a-stamp has not yet boomeranged back to the United States but one could imagine myriad developed-world applications beginning with self-monitoring for disease or for medication compliance.

Diagnostics For All paper “diagnostics lab”, offering high precision coupled with low cost and robustness required of deployment in “resource-poor settings”

Voxiva: Taking “mHealth” (“mobile health”) to the developing world – and back

Voxiva is one of these U.S.-based innovators that started out serving healthcare providers and patients in developing countries and has already made the leap back to the developed world. The company started in 2001 deploying mobile phones for public health with its disease-outbreak reporting system. Speaking at WHCC, William Warshauer, Voxiva’s Executive Vice President, pointed out that mobile phones are a game-changing technology in public health. By the end of 2010, 90% of people in the world will be living within reach of a cell phone signal. Voxiva anticipated this trend, and has built a range of platforms that use cell phones to address health needs. The company first established the HIV/AIDS health management system in Rwanda which helps that country manage drug stocks and avoid the type of shortages that once plagued them regularly. The power of wireless, Warshauer points out, is that you can not only pull information from multiple sites, you can also push it. The health care worker who is reporting the number of vaccines distributed can get a message back saying “your district is 15th in terms of vaccination rate.”

Boomerang: Recently, Voxiva launched its first service in the United States. Text4baby promotes safe motherhood among lower income women. The service is free to the users because mobile carriers have donated the messages. Women are asked for their due date and zip code and then get three messages a week.

These reports resonate with project work CBT Advisors did last year about how innovations in telemedicine were likely to find their way to the market. Our overpowering conclusion from that assessment was that iPhone apps, distance treatment by physicians and all manner of new services were being introduced both in the developed and developing worlds. But virtually none of it was being reimbursed! The innovation was finding its way to the end users with very little intermediation. And consumers outside of highly regulated countries like the United States were likely to derive earlier advantage from it.

Escaping the morass

While non-profits and for-profits avidly mine developing nations for future health solutions, what do companies here do? Plenty, obviously. But they are plagued by a morass of regulations, some well-meaning and efficient and some just stifling, imposed by a large number of federal and state agencies (HIPAA and FDA to name just two). We attended another conference in Cambridge, this one sponsored by Xconomy and held at the MIT Media Lab. See Xconomy’s report on the conference here.

What caught our attention was how many of the innovations featured at this star-studded conference were “workarounds” for some of the more outdated U.S. regulations. Two excellent examples of this are fax transmission of medical records and transmission of images only on CDs, not over the internet. Most physician offices still do it this way in order to comply with patient privacy regulations under so-called HIPAA rules. Thus the fax and CD have been “locked in.” Other transmission methods might be permitted under the regulations but compliance is so cumbersome that they have not yet been widely implemented.

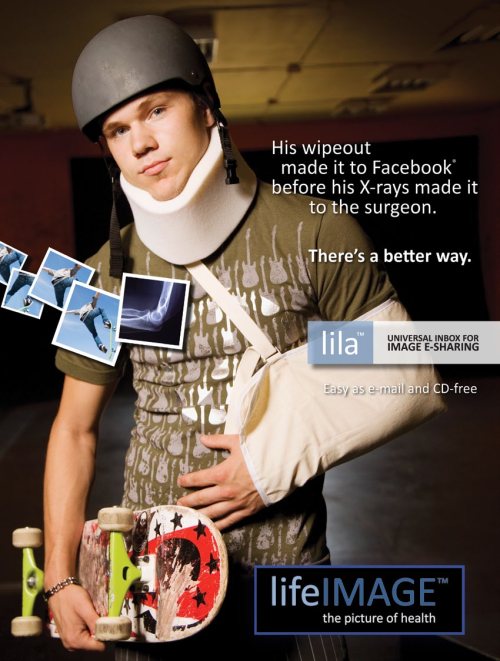

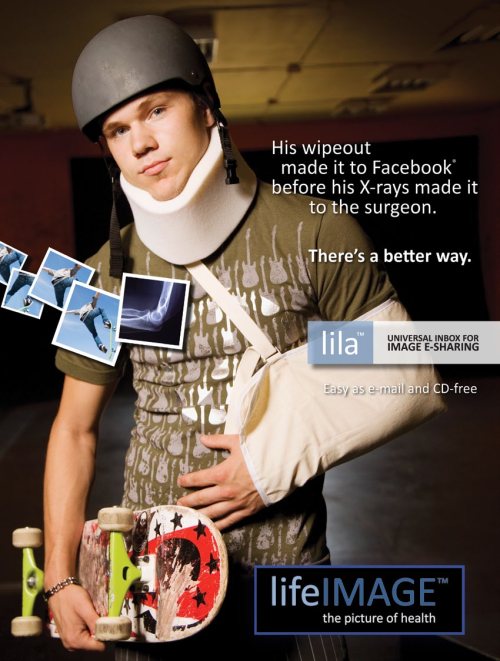

Hamid Tabatabaie, CEO of Life Image, is focused on providing technology to cut costs for storage and sharing of images, and at the same time improving image quality. One billion medical images are expected to be taken annually in the United States by 2012, with waste that Tabatabaie estimates at $15 billion to $20 billion a year due to repeat imaging. Related to that is the lack of image management abilities in the form of networks for storage, retrieval and sharing of images.

At the Xconomy conference, Tabatabaie showed a slide of a skateboarder and an X-ray image. “We’re here to fix the problem that this guy’s buddies on Facebook saw his wipeout before his surgeon saw his X-ray,” Tabatabaie said. Typically, images are passed around the U.S. health care system on CDs. But many of these CDs never reach the right hands, or don’t work when they get there, which leads to repeat imaging. Life Image, a Massachusetts-based, venture-backed company is like a home page for images. Access to the images is tightly controlled, but once a physician is granted access, she needs only to click a mouse to see them. It has been adopted in nine northeastern U.S. hospital groups and now the company is expanding to Florida.

'His wipeout made it to Facebook before the X-rays made it to the surgeon'

So to put it bluntly, developing-worlders innovate to improve care; we innovate to overcome our own bureaucracy.

Innovation inching closer all the time

Going back to boomerangs: which technologies are likely to turn up soonest on U.S. shores? Some higher-cost technologies are here already. As Christensen pointed out in his talk at WHCC, Pfizer and General Electric (GE) are creating many of their innovative products for the developing world, where there is less regulation to get in the way, and then bringing them to the United States and Europe years later. Last year, GE CEO Jeffrey Immelt published an article in Harvard Business Review (“How GE is Disrupting Itself”), outlining why, in healthcare and other markets, GE is pursuing what he and his co-authors dubbed “reverse innovation”. He cited two products that have already boomeranged, a “$1,000 handheld electrocardiogram device and a portable, PC-based ultrasound machine that sells for as little as $15,000.” Both were “originally developed for markets in emerging economies (the ECG device for rural India and the ultrasound machine for rural China) and are now being sold in the United States, where [GE is] pioneering new uses for such machines. They are part of a $3 billion initiative of GE to introduce technologies in the United States that actually lower healthcare costs.

And some of even the more technology- and physician-intensive procedures – think heart surgery – that developing-world-based pioneers have taken on are moving closer to that key milestone. Witness this Nov. 25, 2009 Wall Street Journal piece.

It described the growing franchise of Dr. Devi Shetty, whose hospitals in India perform huge numbers of heart bypass operations (officially called coronary artery bypass graft or CABG) at a price point of $2,000, just a bit below the typical $50,000 to $100,000 charged by Western hospitals – with a lower mortality rate. Dr. Shetty is planning to build and run a new hospital in the Cayman Islands, an hour away from Miami by plane, offering surgeries at a middle-level price point.

Besides heart surgery, what other technologies will arrive soon? The intersection of smartphones and personal health monitoring is one sweet spot. Self-administered diagnostics (think home pregnancy and home HIV testing) and treatment compliance monitoring could be another.

Eventually, maybe even in less than twenty years, market forces are going to even things out. Pricing of healthcare is just so arbitrary and, at least in the United States, so unrelated to value. Yunus has said he hopes to build a health care system that provides quality care so cheaply “even Westerners will want to use it.”

Reading The Innovator’s Prescription again in the wake of healthcare “reform,” we are struck by the observation that there is virtually no reason for any health care provider in the United States to lower prices. Indeed, Harvard’s Christensen wrote, affordable innovation virtually always arises outside of standard systems including healthcare. And the Obama healthcare reform has more or less cemented into place the misplaced incentives. In the book, Christensen identified eight different categories of U.S. healthcare regulation that “now impede disruption and must be changed” (page xliii) i.e. that these regulations are preventing innovation from taking hold. But insurance reform did not affect even one of them! Maybe that’s why he sounded so frustrated in his talk. It’s as if every “must” in the book has been replaced with “won’t.”

So in the United States, we have well-meaning but strangling regulation. Elsewhere, there is rampant innovation. We think we know which will win. One way or another, the innovation we are noticing overseas will soon reach US consumers in ways that will be both remarkable and necessary.

# # #

*Malorye Allison is a Boston-based freelance writer who writes and blogs regularly about innovations in healthcare.